Japanese Pickles (Tsukemono)

CONTENTS

Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

CONTENTS

Menu

Japanese pickles possess a deep history, culture, and purpose that extends far beyond being mere food items.

Understanding the unique flavors and backgrounds of each pickle allows for an even greater appreciation of the depth of Japanese food culture.

Japanese pickles, known as tsukemono, are foods made by preserving vegetables in various seasonings such as salt, rice bran, miso, soy sauce, vinegar, and sake lees, thereby enhancing their shelf life and creating unique flavors and textures. Tsukemono are not merely side dishes; they are an indispensable and deeply rooted part of the Japanese diet.

Definition and Production Methods of Tsukemono

Tsukemono are processed foods primarily made from vegetables. Their preservation is enhanced either by harnessing the power of microorganisms for fermentation or by utilizing the osmotic pressure of various seasonings. The production methods are diverse, varying significantly by region and the ingredients used.

Here are the main pickling beds (ingredients used for pickling)

Koji produces a vast array of powerful enzymes (amylase, protease, lipase, etc.). These enzymes break down proteins, starches, and fats in ingredients into amino acids, sugars, and fatty acids, respectively. This process is essential for:

- Salt: Used for Shiozuke (e.g., Nozawana-zuke, some types of Umeboshi).

- Rice Bran: Used for Nuka-zuke (e.g., cucumber nuka-zuke, daikon nuka-zuke).

- Miso: Used for Miso-zuke (e.g., daikon miso-zuke, Nasu Dengaku).

- Soy Sauce: Used for Shoyu-zuke (e.g., Fukujinzuke, rakkyo-zuke).

- Vinegar: Used for Su-zuke (e.g., Beni Shoga, amazu-zuke).

- Sake Lees: Used for Kasu-zuke (e.g., Narazuke, fish kasu-zuke).

- Koji: Used for Koji-zuke (e.g., Bettara-zuke).

- Sugars: Used for Sato-zuke (e.g., some fruit pickles).

Ancient History

The history of tsukemono is incredibly old, forming a fundamental part of Japanese food culture.

From the Yamato Imperial Court to the Heian Period (8th-12th Century):

The oldest records of tsukemono date back to the Nara period (around the 8th century), with descriptions of salt-pickled vegetables found in the Man’yōshū anthology. Furthermore, the Engishiki, a legal code compiled during the Heian period (early 10th century), lists various types of tsukemono presented to the imperial court, indicating that diverse pickles already existed by this time.

Wisdom of Food Preservation:

In an era without refrigeration technology, tsukemono represented invaluable wisdom for the long-term preservation of harvested vegetables, essential for securing food supplies, especially during winter. Salt-pickling was the most primitive method, followed by the development of more flavorful pickles like nuka-zuke and miso-zuke.

Diverse Roles and Functions

Tsukemono are not merely preserved foods; they fulfill various roles in Japanese daily life.

Enhanced Nutritional Value:

During the fermentation process, microorganisms like lactic acid bacteria work to increase nutrients such as B vitamins and amino acids, and can also promote digestion and absorption.

Appetite Stimulation:

The appropriate saltiness, tartness, and complex umami stimulate the appetite, making rice more enjoyable. Fermented pickles like nuka-zuke, in particular, have a unique aroma that entices eating.

Palate Cleanser / Hashiyasume:

Eaten after rich or heavily flavored dishes, tsukemono refresh the palate, allowing subsequent dishes to be savored more deliciously. They also play a role in balancing the overall meal.

Color and Presentation:

With vibrant colors like the red of umeboshi or the green of cucumbers, tsukemono add visual appeal to the dining table, enriching the meal experience.

Contribution to Health:

Pickles rich in probiotics, such as lactic acid bacteria (e.g., nuka-zuke), are said to contribute to improving gut health.

Remarkable Diversity

The varieties of Japanese pickles have developed uniquely to suit the local specialty vegetables, climate, and culture of each region.

A wide variety of types:

As commonly stated, “there are over 600 varieties across Japan,” meaning many pickles with distinct regional characteristics exist. For example, Kyoto’s Suguki-zuke and Senmaizuke, Akita’s Iburigakko, Hiroshima’s Hiroshimana-zuke, and Nagano’s Nozawana-zuke are just a few of the numerous local pickles.

Relationship with climate:

Connection to Local Climate and Culture: Tsukemono in each region are closely tied to the local climate, specialties, and people’s lifestyles. For instance, in snowy regions, a culture of pickling large quantities of daikon radishes and turnips developed as a way to prepare for winter.

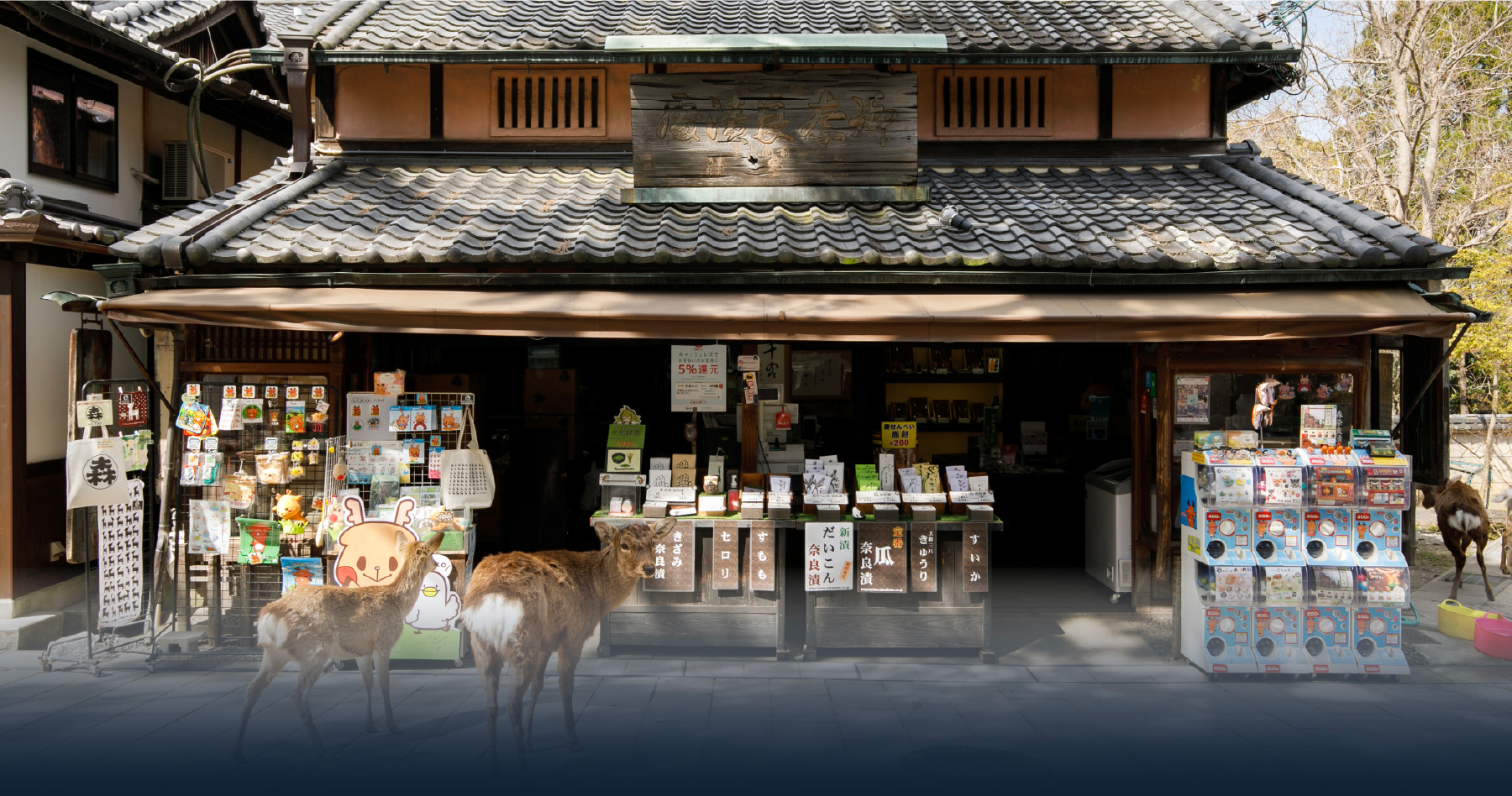

Store Information

23 Kasuganocho, Nara city, Nara pref., 630-8212, Japan

(In front of the South Gate of Todaiji Temple)

Hours: 9:00 – 18:00 (extended during events)

Closed: open everyday

Google MAP