Characteristics of

Japanese Fermented Foods

CONTENTS

Menu

Menu

Menu

Menu

CONTENTS

Menu

In essence, Japanese fermented foods are a testament to how specific microorganisms, when nurtured by a unique environment and ingenious human techniques, can transform simple ingredients into a complex, delicious, and healthy culinary heritage.

The most defining characteristic of Japanese fermented foods is undoubtedly the use of koji (malted rice). Japan’s warm and humid climate, along with its abundant marine environment providing salt, has historically supported the development of these unique foods. Japanese fermented foods represent a culinary culture born from the fusion of fermentation techniques utilizing koji mold and Japan’s distinctive climate and natural features. Their diversity, versatility, and blend of tradition and innovation are among the proudest attractions of Japanese food culture to the world.

The Central Role of Koji

Koji (specifically, Aspergillus oryzae) is the cornerstone of most Japanese fermented foods. Unlike many other fermented foods globally that rely primarily on bacteria or yeast, koji mold plays a unique and crucial role in Japan.

Enzyme Powerhouse:

Koji produces a vast array of powerful enzymes (amylase, protease, lipase, etc.). These enzymes break down proteins, starches, and fats in ingredients into amino acids, sugars, and fatty acids, respectively. This process is essential for:

Developing Umami:

The breakdown of proteins into amino acids, especially glutamates, is what gives Japanese fermented foods their rich and deep umami flavor.

Creating Sweetness:

Starches are converted into sugars, contributing to the characteristic sweetness of products like sake and mirin.

Enhancing Aroma:

he enzymatic reactions also produce a complex array of aromatic compounds.

Foundation for Key Ingredients:

- Koji is indispensable for making:Miso: Fermented soybean paste, a staple seasoning. Soy Sauce: The primary condiment, made from soybeans and wheat.

- Sake: Japan's national alcoholic beverage.

- Mirin: A sweet cooking sake.

- Amazake: A sweet, low-alcohol or non-alcoholic fermented rice drink.

- Shio Koji: A versatile seasoning made from koji, salt, and water.

Climate and Geography as Catalysts

Japan’s unique geographical and climatic conditions have profoundly influenced its fermentation culture.

Warm and Humid Climate:

This environment is ideal for the propagation of koji mold and other beneficial microorganisms essential for fermentation. The humidity helps maintain moisture levels necessary for microbial activity.

Abundant Salt from the Ocean:

As an island nation, salt has always been readily available. Salt acts as a preservative, controlling unwanted microbial growth while allowing desirable fermentation to occur. It’s a critical component in miso, soy sauce, and various pickles.

Rich Biodiversity:

The diverse ecosystem provides a variety of raw materials (rice, soybeans, vegetables, seafood) and the specific microbial strains suited for local fermentation processes.

Diversity and Versatility

Japanese fermented foods are incredibly diverse in their forms, flavors, and applications.

Wide Range of Products:

From liquid seasonings (soy sauce, mirin) and pastes (miso) to beverages (sake) and solid foods (tsukemono/pickles, natto), the variety is immense.

Culinary Backbone:

They are not just side dishes; they are fundamental to Japanese cuisine, forming the basis of broths (like dashi made with miso), marinades, dressings, and general seasoning. Their versatility allows them to enhance almost any dish.

Tradition and Innovation

Japanese fermented foods are deeply rooted in centuries-old traditions, passed down through generations. However, this tradition is not static.

Preservation of Ancient Methods:

Many artisanal producers still use traditional techniques, often involving long fermentation periods and natural aging in cedar barrels.

Continuous Innovation:

There’s ongoing research and development into new fermentation processes, healthier versions (e.g., low-salt miso), and innovative applications in modern cuisine and health products. This blend of respect for tradition and a drive for innovation keeps the culture vibrant and relevant.

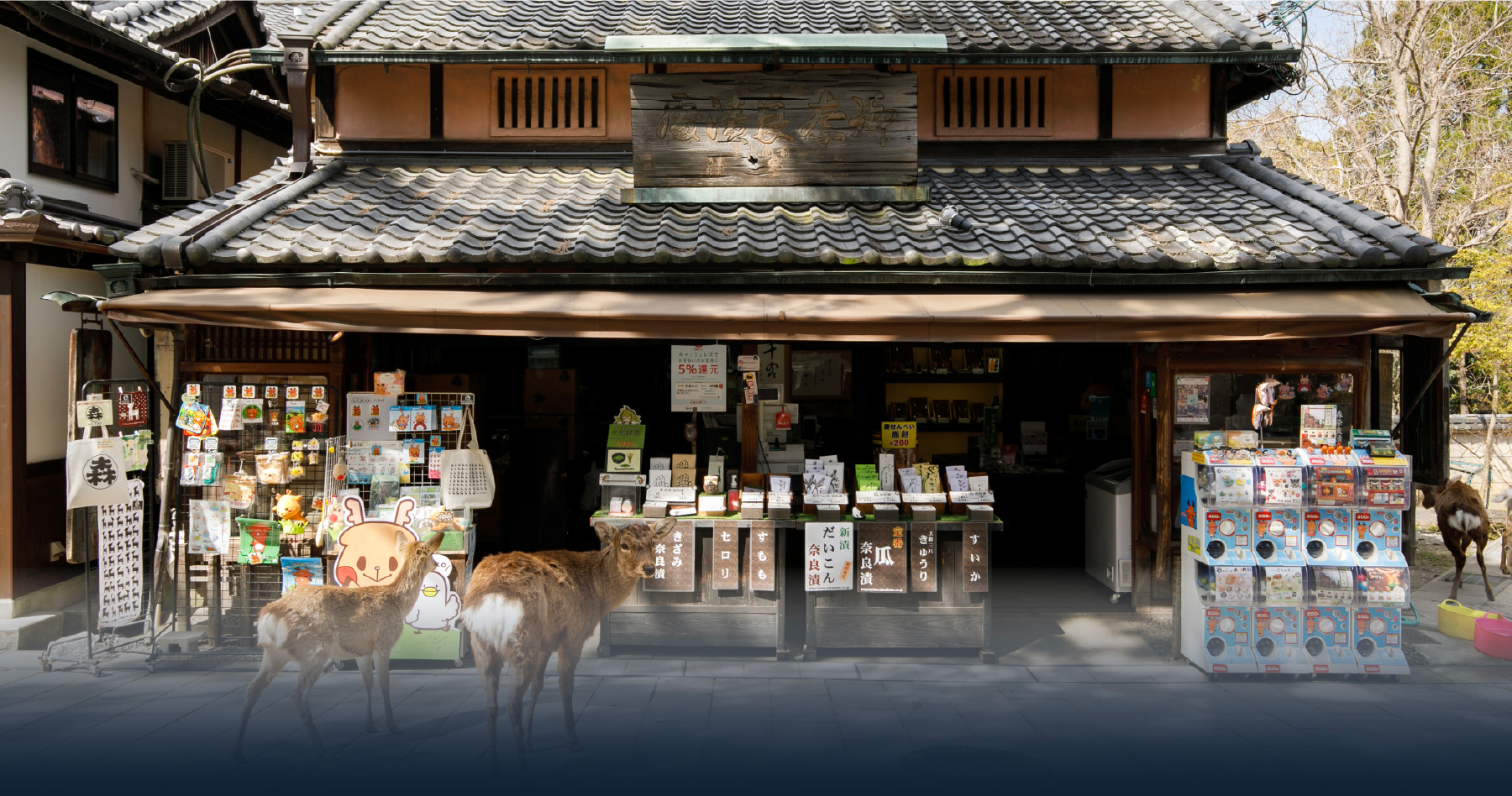

Store Information

23 Kasuganocho, Nara city, Nara pref., 630-8212, Japan

(In front of the South Gate of Todaiji Temple)

Hours: 9:00 – 18:00 (extended during events)

Closed: open everyday

Google MAP